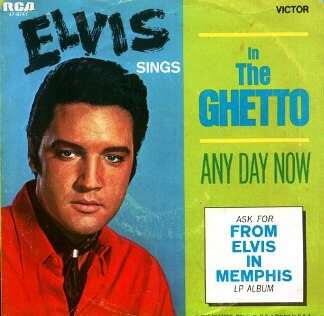

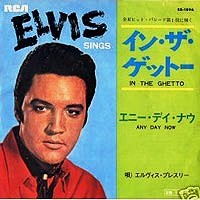

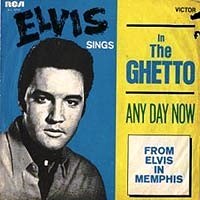

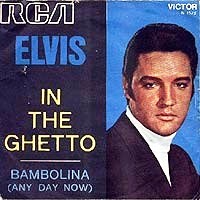

'In The Ghetto' / 'Any Day Now'

RCA Single 47-9741

Released April 14 1969.

Recorded January 20 1969 at American Studios, Memphis

Memphis had always been a polarised town having its roots in the music of the slaves. It is the unmistakable musical blend of black and white, rural and urban, which gave rise to Memphis' reputation, starting nearly 100 years ago, as a major music centre. In the soulful heyday of the sixties, black and white musicians worked together round-the clock to create music that would change the world - with STAX Studios at its epicentre.

However Memphis was politically rocked on its very foundations when American black civil rights leader Dr Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4th 1968 while helping to organise a march of sanitation workers protesting against low wages and poor working conditions. King’s assassination led to riots in over 60 American cities including Chicago and Washington.

So less than a year later in January 1969 when Elvis found himself in Chips Moman's ‘American Studios’ situated on the rougher side of town, racial relations were still on edge. Memphis Horns player Wayne Jackson recalled, "It was tense, especially in the parts of town that were mainly black, where STAX and American Sound were. The studio was guarded by dogs, and there was a man on the roof with a gun minding the parking lot."

Elvis arrived at American on 13 January 1969, fresh from the rejuvenating success of the NBC TV Special and with `If I Can Dream' riding high in the charts, but he was as nervous about the forthcoming ten-day session as he had been about his recent television appearance.

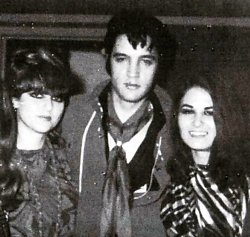

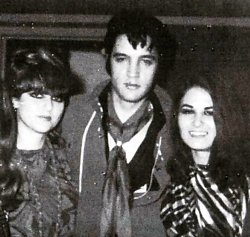

(Right: Elvis in American Studios with Back Up vocalists Jeannie Greene and Donna Thatcher. January 20th 1969.)

|

|

For the first time in a decade Elvis was escaping from the routine comfort of working in his standard work places of RCA studios in Hollywood and Nashville. With Chips Moman’s American Sound Studios – recommended by friend Marty Lacker – Elvis found himself among experienced session-men who were not in awe of him. His nervousness was apparent and he would experience vocal problems due to the on-set of Laryngitis. Some of the session musicians were possibly disappointed that the scheduled Neil Diamond session had been cancelled to make way for Elvis. But in the event Elvis found a creative groove during that first ten-day burst that would never be bettered. These pivotal 969 recording sessions at American Sound now rank alongside the seminal Sun sessions and pivotal RCA Nashville recordings.

Despite the presence of great studios nearby this would be the first time since the classic SUN Studio sessions that Elvis was back in a Memphis recording studio. And in 1969 recording at American Sound Studios also carried a real prestige. Recently British singer Dusty Springfield had cut her classic Dusty In Memphis album there while the studio had also released plenty of chart successes by stars such as Wilson Pickett, Dionne Warwick and The Box Tops.

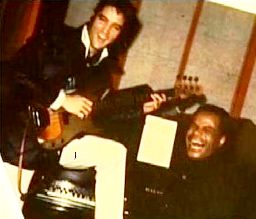

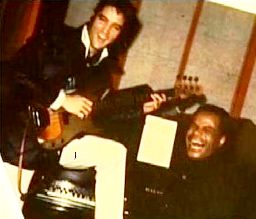

(Right: Rare candid of Elvis and singer Roy Hamilton at American Studios.)

|

|

It wasn't just the studio or the musicians, or the euphoria at having escaped from his recent rut. Elvis was really getting off on the new music - songs by young songwriters like Mac Davis, Mark James and Eddie Rabbitt were striking a real chord with him. And after years of being numbed by mediocrity, Elvis was finally getting back in touch with his instincts.

In the end it was because of Marty's unhappiness over the lack of challenge Elvis would find in the regular Nashville setting that he managed to persuade Elvis to go to Chip Moman's studios, but only at the last minute.

The situation at the time is described by Marty Lacker...

... I'd go up to Graceland and Elvis would start playing demos of sessions that he did, and the stuff was just terrible. He hadn't had a Top 5 record since 1965, and that was "Crying in the Chapel," which was basically a gospel song.

I told him about Chips Moman and the stuff he was cutting at American Studios, and I told him I thought they'd be great together. He said, "Well, I'll think about it." That was it.

(In the end) I had only four days to set it all up. And I knew that Chips had Roy Hamilton, who was one of Elvis's idols, scheduled to record that day and Neil Diamond scheduled for Monday night.

I went out in hall and phoned Chips at home. I said, "Lincoln," which is his real name. "I'm up at Graceland. Would you still like to cut Elvis?" And he said, "Don't be playing games with me. You know how bad I want to do that." I said, "I'm not joking. He wants to cut here in Memphis, and he wants to cut with you." I said, "But you got one little problem. He's got to start Monday night, and that's when Neil Diamond's in there." Chips's exact words were, "F*** Neil Diamond. Neil Diamond will just have to be postponed. Tell Elvis he's on."

I had one more thing to do, which was the hardest part. And I phrased it in a way where I knew Elvis wouldn't get upset. I said, "I need to ask you to do me a favor. You're going to have six of the best musicians in the recording business. The studio is great, the producer's great. And we all know you can sing. So please, would you get some good songs." Elvis said, "Well, I was going to play you some stuff that I got out in California. It's from this really odd guy."

When Elvis was doing Speedway, Nancy Sinatra introduced him to Billy Strange, who ended up cowriting several songs with Mac Davis that Elvis recorded, like "Memories" and "Nothingville," on the Singer Special soundtrack. Billy was also the musical director on Live a Little, Love a Little, and The Trouble with Girls. He told Elvis he had a great songwriter he wanted him to meet.

Elvis told me he walked into the room, and this guy was sitting in the corner on the floor, playing guitar and singing these songs. And that there was no damn furniture in the room. The guy's name was Scott Davis, but he went by "Mac." And Mac Davis played Elvis "In the Ghetto" and "Don't Cry Daddy."

That first night at American, Elvis cut "Long Black Limousine," "This Is the Story," and "Wearin' That Loved on Look." And Chips was totally in control. Elvis wanted this album to be a hit so bad. And he'd never really worked with a producer before. Elvis would be the one to say, "No, I don't like this take. Let's do it again." But Chips would stop him in the middle and say, "Hey, that didn't sound right, Elvis. You need to do it again. You can do it better than that."

A lot of people thought Elvis was going to blow up and say, "Let's get the hell out of here." But Elvis listened, and Chips got him to do a lot of things because Elvis was receptive at that point. And the musicians were really getting into it, and Elvis was loving it. The really big hits that Elvis cut during the Memphis Sessions"Don't Cry Daddy," "In the Ghetto," "Suspicious Minds"- were all created in that studio by Elvis, Chips, and the musicians - as opposed to old routine of aping what was on the demo.

At one point, in the beginning of the session, Elvis was concerned about recording In The Ghetto. He had never done what might be considered a message song and had often said he did not want to get into this type of music.

We discussed the matter quite thoroughly and I finally said to Elvis "I really don't think it will hurt you. It's a good song."

Chips agreed and Elvis agreed, and In The Ghetto was recorded in the session.

It would be a challenge since in a decade as politically hypersensitive as the 1960s, most white multi-millionaires singing about cold grey mornings in Chicago ghettos would have sounded, at best, patronising and, at worst, like a bad joke.

According to Wayne Jackson, the doubts disappeared as soon as Elvis started to sing: "we were actually in the ghetto, and here was Elvis singing a pertinent song about the South and the social climate of the day ... chills went all over me."

Elvis' commitment to both song and subject is obvious in the sensitivity and strength of his voice. His immaculate phrasing gently underlines the double meaning of "well the world turns", while when the boy dies at the end, he sings not with sentimentality but with compassion. It is a consummate performance, accentuated by the grim drum rolls and the backing singers, who sound for all the world as though they are accusing the audience.

With the recent chart successes of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Simon and Garfunkel and Peter, Paul & Mary, "protest music" was already an integral part of the music scene by 1969. Elvis had even tried out Dylan's Blowin' In The Wind' at home, but in the end decided to restrict his protests to complaining to Colonel Parker about the quality of the material he was expected to sing.

|

|

|

Above: Other worldwide 45 RPM covers

`In the Ghetto' was the song that really confirmed Elvis' musical renaissance. He obviously responded to the song's sentiments and the American Sound musicians locked on to the beat from early on - but Elvis cared enough about this song to spend 23 takes getting it just right.

The song's original title, 'The Vicious Circle', was thought too strong for Elvis; but while the title may have been softened, the strength of his performance on the finished song was evident. America had been riven by violent confrontation throughout the 60s: race riots had torn apart Los Angeles and anti-Vietnam demonstrations raged nationwide. But `In The Ghetto' wasn't a call to arms, rather a gentle reflection in the vein of Dylan's 'Blowin' In The Wind' or Sam Cooke's 'A Change Is Gonna Come'.

From the very first take, Elvis' singing on 'In the Ghetto' was as fine as at any time in his career. The song develops and builds bass and guitar pick out the melody; the drums are staccato and military; while the backing vocals offer call and response to the pleading vocal, sounding eerie and otherworldly, affecting in a way that the comforting 'doo-doo' accompaniment of The Jordanaires would never be again. But in the end the song is carried by the heroic vocal with Elvis injecting drama, pain, poignancy and hope in a way that nobody else ever could.

Take 23 was the exquisite single Master, with the Backing Vocals & overdubs added later.

However to truly feel the emotional impact of the song one should also listen to Take 11 as featured on the FTD ‘Memphis Sessions’. Without the overdubs, EIvis’ vocal is even purer and it sounds even better than the original single! The brilliant audio mix takes the story to new emotional level. So poignant and quite beautiful.

Do listen to both versions on headphones.

Music doesn't get any better.

Spotlight by Piers Beagley.

-Copyright EIN 14th April 2009. Do Not reprint or republish without permission.

Spotlight References:

Writing For The King – Ken Sharp

Revelations of the Memphis Mafia – Alanna Nash

Rough Guide To Elvis – Paul Simpson

The 31 Hits - Patrick Humpries

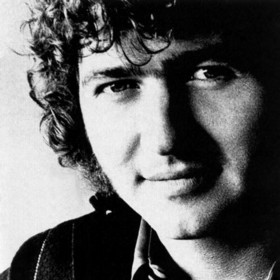

Mac Davis was one of Elvis Presley’s most-important songwriters.

Ken Sharp author of ‘Writing For The King’ spent a while talking with Mac Davis who revealed not only his inspiration for writing these incredible songs but also the delight he had in spending time with Elvis.

|

|

Mac Davis: My daddy was a small building contractor. There was a guy named Alan Smith that had worked for him for years and years. He was just like part of the family. He was a black man and his little boy, Smitty Junior, was my age and he and I used to play together. They lived in a really funky dirt street ghetto. The term 'ghetto' had started to become popular to describe the urban slums.

Smitty Junior lived in a part of Lubbock called Queen City. They had dirt streets and broken glass everywhere. I couldn't understand how these kids could run around barefoot on all that broken glass, I was wondering why they had to live that way and I lived another way. Even though we weren't wealthy or anything it was a whole big step up from the way that Smitty Junior had to live.

A friend of mine, Freddy Weller, showed me a lick on the guitar. He was playing for Paul Revere & the Raiders at the time. I was messing around with it after he left and I just went (sings) "In the ghetto." I thought, man, that just fits. I had always wanted to write a song called "The Vicious Circle." There's nothing that rhymes with circle, if you wanna know the truth about it.

A child is born in a situation, his father leaves and he ends up acting out and becoming his father. Being born and dying and being replaced by another child in the same situation is basically what I was talking about. Dying is a metaphor for being born into failure. Being born into a situation where you have no hope. If you listen to the song it's more poignant now than it was then. Instead of getting better it's gotten worse. Back then we had gangs and violence in a few cities, now we have it in almost every American city.

I called Freddy Weller in the middle of the night and played it for him. I did that with a lot with people. Everybody who was a friend of mine in those days can tell you that they got woken up a lot because I would call and sing them some miserable, sad sumbitch that I had written. When I had finished the last line in "In The Ghetto," I knew that I had written a hit. I didn't know that it was important but I just knew that it was a hit if the right person cut it.

I think Elvis took a huge chance in doing "In The Ghetto." It was a big risk. When they released it I was totally surprised that he saw fit to put that out as a single. That was not his image at all. He was always middle of the road when it came to controversy. The Colonel was on top of all of that stuff.

One of the things Elvis told me the first night I went over to his house was, "You know what I would like to do more than anything in the world?" And said, "What?" He said, "I wanna be on Laugh-In." I said, "You're kidding me? You wanna be on Laugh-In?"" He said, "Yeah. I wanna put on that little yellow raincoat and get on a tricycle and ride around in a circle and come up to the camera, raise my head up and go, "Sock it to me" - Don't you think that would be great?" I said, would probably be on the front page of the newspapers the next morning. Why don't you do it?" He said. "Colonel won't let me." I said, "Why?" He said, "Well. the Colonel just won't let me do it. It's not good for my career." I was shocked that the Colonel allowed him to put out "In The Ghetto" because it was controversial at the time. But I'm glad he did.

Elvis improved on "In The Ghetto." In fact, it was Elvis' idea to add another "and his mama cries" at the end of that song. I didn't write that in there originally. The song originally finished (sings) "And another little baby child is born ...in the ghetto." That was the end of it. Elvis threw in (sings) "and his mama cries." To me the circle had been done but he just emphasized it by saying "and his mama cries" again. I think he definitely improved it by doing that. It would have been a hit without him doing it but I still think he improved it.

All of a sudden I had my first number one record with "In The Ghetto." I was able to change my name back to Mac Davis instead of Scott Davis, which I wrote under for a while because Hal David's brother's name was Mack David. As a matter of fact, "A Little Less Conversation" was under Scott Davis originally. The success of "In The Ghetto" opened doors to me as an artist too.

_____________________________________________

'In The Ghetto'

(Lyrics & Music by Mac Davis)

As the snow flies

On a cold and grey Chicago mornin'

A poor little baby child is born

In the ghetto

And his mama cries

'cause if there's one thing that she don't need

it's another hungry mouth to feed

In the ghetto

People, don't you understand

the child needs a helping hand

or he'll grow to be an angry young man some day

Take a look at you and me,

are we too blind to see,

do we simply turn our heads

and look the other way

Well the world turns

and a hungry little boy with a runny nose

plays in the street as the cold wind blows

In the ghetto

And his hunger burns

so he starts to roam the streets at night

and he learns how to steal

and he learns how to fight

In the ghetto

Then one night in desperation

a young man breaks away

He buys a gun, steals a car,

tries to run, but he don't get far

And his mama cries

As a crowd gathers 'round an angry young man

face down on the street with a gun in his hand

In the ghetto

As her young man dies,

on a cold and grey Chicago mornin',

another little baby child is born

In the ghetto.. .. and his mama cries

Click here to comment on this article

Go here for the complete Ken Sharp interview with Mac Davis